I know that conferences like NeurIPS (formerly called NIPS) have asked for statements about ethical and "broader impact" to accompany papers submitted to them. In principle I am all for this since it's always good for scientists to think about the social implications of the work. I also read the details of the requirements and they aren't draconian, especially for highly theoretical papers whose broader impact is far from clear.

Some thoughts on "broader impact" statements for scientific papers

Book Review: "His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life" by Jonathan Alter

I first saw Jimmy Carter with a few other students during my first year as a graduate student at Emory University where he remains a visiting professor - I still remember the then 81-year-old briskly striding in with his signature broad, toothy smile and the energy of a man half his age. The amusing thing was that when he opened up the floor to any question that we wanted to ask him, the first question someone asked right away was whether LBJ was responsible for JFK's assassination. Without batting an eyelid Carter said no and moved on.

Book Review: "The Jews of Spain", by Jane Gerber

Jane Gerber’s “The Jews of Spain” is a superb and comprehensive look at the history of the Sephardim - one of the two major branches of Jewry, the other being the Ashkenazim. The Sephardim originated in Spain and today occupy a place of high prominence. While the Ashkenazim are better known, about sixty percent of Israel’s population consists of the Sephardim.

Book Review: "The Pity Of It All: A Protrait of the German-Jewish Epoch", 1743-1933, by Amos Elon

Amos Elon’s ‘The Pity of It Al’ is a poignant and beautiful history of German Jews from 1743-1933. Why 1743? Because in 1740, Frederick of Prussia liberalized the state and allowed freedom of worship. The freedom did not extend to Jews who still had no political or civil rights, but it did make it easier for them to live in Prussia than in the other thirty-six states of what later came to be called Germany.

The book begins with the story of the first prominent modern German-Jewish intellectual, the fourteen-year-old, barefooted Moses Mendelssohn, who entered Berlin through a gate reserved for “Jews and cattle”. Mendelssohn was the first Jew to start an enduring tradition that was to both signal the high watermark of European Jewry and their eventual destruction. This was the almost vehement efforts of Jews to assimilate, to convert to Christianity, to adopt to German traditions and ways, to become bigger German patriots than most non-Jewish Germans while retaining their culture and identity. In fact the entire history of German Jewry is one of striking a tortuous balance between assimilating into the parent culture and preserving their religion and identity. Mendelssohn became the first great Jewish German scholar, translating Talmud into Hebrew and having an unsurpassed command of both German and Jewish philosophy, culture and history. While initially he grew up steeped only in German culture, a chance encountered with a Protestant theologian who exhorted him to convert. This encounter convinced Mendelssohn that he should be more proud of his Jewish roots, but at the same time seek to make himself part and parcel of German society. Mendelssohn’s lessons spread far and wide, not least to his grandson, the famous composer Felix Mendelssohn who used to go to Goethe’s house to play music for him.

Generally speaking, the history of German Jews tracks well with political upheavals. After Prussia became a relatively liberal state and, goaded by Mendelssohn, many Jews openly declared their Judaism while forging alliances with German intellectuals and princes, their condition improved relative to the past few centuries. A particularly notable example cited by Elon is the string of intellectual salons rivaling their counterparts in Paris that were started in the Berlin by Jewish women like Rachel Varnhagen which drew Goethe, the Humboldt brothers and other cream of German intellectual society. The flowering of German Jews as well-dot-do intellectuals and respectable members of the elite starkly contrasted with their centuries-old image in the rest of Europe as impoverished caftan-wearers, killers of Christ and perpetuators of the blood libel. Jews had been barred from almost all professions except medicine, and it was in Prussia that they could first enter other professions.

When Napoleon invaded Prussia, his revolutionary code of civil and political rights afforded the German Jews freedom that they had not known for centuries. The Edict of 1812 freed the Jews. They came out of the ghettoes, especially in places like Frankfurt, and the Jewish intelligentsia thrived. Perhaps foremost among them was the poet Heinrich Heine whose astute, poignant, tortured and incredibly prescient poetry, prose and writings were a kaleidoscope of the sentiments and condition of his fellow Jews. Heine reluctantly converted but was almost tortured by his torn identity. The Edict of 1812 met with a tide of rising German nationalism from the bottom, and Jews quickly started reverting back to their second-class status. Heine, along with Eduard Gans and Leopold Zunz who started one of the first scientific societies in Germany, had trouble finding academic jobs. The Hep! Hep! riots that started in Wurzburg and spread throughout Germany were emblematic of the backlash. Significantly, and again in potent portend, this was the first time that German intellectuals took part in the violent anti-Semtism; later when the Nazis took over, the legal basis of their murderous anti-Semtism was undergirded by intellectuals, and it was intellectuals who drew up the Final Solution in 1942 at the Wannsee conference. Jews in record numbers started to convert to escape discrimination.

For the next few decades, straddling this delicate and difficult balance between adopting two identities was to become a hallmark of the Jewish condition in Germany, although scores also converted without any compunction. Writing from Paris in 1834, Heine issued a warning:

“A drama will be enacted in Germany compared to which the French revolution will seem like a harmless idol. Christianity restrained the martial ardor of the Germans for a time but it did not destroy it; once the restraining talisman is shattered savagery will rise again. The mad fury of the berserk of which Nordic Gods sing and speak. The old stony gods will rise from the rubble and rub the thousand year old dust from their eyes. Thor with the giant hammer will come forth and smash the granite domes.”

Extraordinarily prescient words, especially considering the Nordic reference.

The next upheaval came with the European liberal revolution of 1848. As is well known, this revolution overthrew monarchies - temporarily - throughout Europe. For the first time, Germany’s Jews could agitate not just for civil but political rights. A record number of Jews were appointed to the Prussian parliament by Frederick William IV. Unfortunately even this revolution was not to last. Frederick William reneged on his promise, many Jews were either ejected from parliament or made impotent and another rising tide of nationalism engulfed Germany. The next few decades, while not as bad the ones before, sought to roll back the strides that had been made.

It’s in this context that the rise of Bismarck is fascinating. Bismarck dodges many stereotypes. He was the emblem of Prussian militarism and autocracy, the man who united Germany, but also the liberal who kickstarted the German welfare state, pioneering social security and health insurance. When he declared war on France in 1870, patriotic Jews not only took part in the war but funded it. “Bismarck’s Jews” procured the money, helped Bismarck draw up the terms of French capitulation and occupation at Sedan. Among these, Ludwig Bamberger and Abraham Bleichroder were the most prominent - Bleichroder even used stones from Versailles to build a large mansion in Germany. While praising these Jews for their contributions to the war effort, Bismarck stopped short of saying that they should be awarded full rights as citizens of Germany. Nevertheless, in 1871, Bismarck passed an edict that banned discrimination on the basis of religion in all civil and political functions. It seemed that the long-sought goal of complete emancipation was finally in sight for Germany’s Jews.

But even then, as patriotic Jews signed up for the Franco-Prussian War, a dissenting note was struck by another Jew. Leopold Sonnemann was the publisher of a leading Frankfurt newspaper. In editorial after editorial, he issued stark warnings both to Jews and gentiles of the rising militarism and rigid social order in Prussia that was taking over all of Germany. He warned Jews that ironically, their patriotism may cost them more than they bargained for. Sonnemann was another prescient Jew who saw what his community’s strenuous efforts to conform were costing them. Sonnemann’s predictions were confirmed almost right away when a recession hit Germany in 1873 that was among the worst of the previous hundred years. Immediately, as if on cue, anger turned toward the wealthy Jews who had apparently grown fat and rich during the war while their fellow citizens grew impoverished. In 1879, a prominent Protestant clergyman named Adolf Stocker started railing against the Jews, calling them a “poison in German blood”, echoing paranoia that was leveraged to devastating effect by another Adolf a half century later. The Kaiser and Bismarck both disapproved of Stocker’s virulent anti-Semitic diatribes, but thought that it perhaps might make the Jews more “modest”. To say that this was unfair retaliation against a patriotic group who had bankrolled and helped the war efforts significantly would be an understatement.

Even as Bismarck was propagating religious freedom in Germany, anti-Semitic continued to grow elsewhere. Interestingly, in France where Jews had a much better time after Napoleon, Arthur Gobineau published a book arguing for Nordic superiority. About the same time, the fascinating but deadly English-German Houston Chamberlain, son-in-law of Wagner, published the massive “Foundations of the Nineteenth Century” in 1899 that became a kind of Bible for the 20th century pan-German Völkisch movement that fused nationalism with racialism. Both Gobineau and Chamberlain were to serve as major ‘philosophers’ for Hitler and the Nazis. In France, the Dreyfus affair had already exposed how fragile the situation of French Jews was.

As sentiments against the Jews grew again, German Jews again became disillusioned with conversion and conformity. The Kabbalah movement and other mysticism-based theologies started to be propounded by the likes of Martin Buber. Rather than keep on bending over backward to please an ungrateful nation, some sought other means of reform and escape. Foremost among these was the centuries old dream of returning to the promised land. Theodor Herz picked up the mantle of Zionism and started trying to convince Jews to migrate to Palestine. Ironically, the main target of his pleas was the Kaiser. Herzl wanted the Kaiser to fund and officially approve Jewish migration to Palestine. Not only would that reduce the Jewish population in Germany and perhaps ease the pressure on gentiles, but in doing so, the Kaiser would be seen as a great benefactor and liberator. In retrospect Herzl’s efforts have a hint of pity among them, but at that time it made sense. The ironic fact is that very few German Jews signed on to Herzl’s efforts to emigrate because they felt at home in Germany. This paradox was to prove to be the German Jews’ most tragic quality. Where Herzl sought emigration, others like Freud and Marx (who had been baptized as a child) sought secular idols like psychoanalysis and communism. This would have been a fascinating theme in itself, and I wish Elon had explored it in more detail.

As the new century approached and another Great War loomed, the themes of 1870 would be repeated. The ‘Kaiserjuden’ or Kaiser’s Jews, most prominently Walter Rathenau, would bankroll and help Germany’s war with England and France. Many Jews again signed up or patriotic duty. Without Rathenau, who was in charge of logistics and supplies, German would likely have lost the war within a year or two. Yet once again, the strenuous efforts of these patriotic Jews were forgotten. A young Austrian corporal who had been blinded by gas took it upon himself to proselytize the “stab in the back” theory, the unfounded belief that it was the Jews who secretly orchestrated an underhanded deal that betrayed the army and cost Germany the war. The truth of course was the opposite, but it’s important to note that Hitler did not invent the myth of the Jewish betrayal. He only masterfully exploited it.

The tragic post-World War 1 history of Germany is well known. The short-lived republics of 1919 were followed by mayhem, chaos and assasinations. The Jews Kurt Eisner in Bavaria and Walter Rathenau were assasinated. By that time there was one discipline in which Jews had become preeminent - science. Fritz Heber had made a Faustian bargain when he developed poison gas for Germany. Einstein had put the finishing touches on his general theory of relativity by the end of the war and had already become the target of anti-Semitism. Others like Max Born and James Franck were to make revolutionary contributions to science in the turmoil of the 1920s.

Once the Great Depression hit Germany in 1929 the fate of Germany’s Jews was effectively sealed. When Hitler became chancellor in 1933, a group of leading Jewish intellectuals orchestrated a massive but, in retrospect, pitiful attempt to catalog the achievements of German Jews. The catalog included important contributions by artists, writers, scientists, philosophers, playwrights and politicians in an attempt to convince the Nazis of the foundational contributions that German Jews had made to the fatherland. But it all came to nothing. Intellectuals like Einstein soon dispersed. The first concentration camp at Dachau went up in 1936. By 1938 and Kristallnacht, it was all over. The book ends with Hannah Arendt, protege of Martin Heidegger who became a committed Nazi, fleeing Berlin in the opposite direction from which Moses Mendelssohn had entered the city two hundred years earlier. To no other nation had Jews made more enduring contributions and tried so hard to fit in. No other nation punished them so severely.

Book Review: "Against the Grain", by James Scott

James Scott's important and utterly fascinating book questions what we can call the "Whig view" of history, which goes something like this: At the beginning we we were all "savages". We then progressed to becoming hunter gatherers, then at some point we discovered agriculture and domesticated animals. This was a huge deal because it allowed us to became sedentary. Sedentism then became the turning point in the history of civilization because it led to cities, taxation, monarchies, social hierarchies, families, religion, science and the whole shebang of civilizational wherewithal that we take for granted.

Two views of America

The United States is a country settled by Europeans in the 17th and 18th century who created a revolutionary form of government and a highly progressive constitution guaranteeing freedom of speech, religion and other fundamental human rights which could be modified. It was a development unprecedented both in space and time.

At the same time, this creation of the American republic came at great cost involving the displacement and decimation of millions of Native Americans and the institution of chattel slavery on these lands. The original constitution had grave deficiencies and it took a long time for these to be remedied.

Many people can’t hold these two very different-sounding views of America in their minds simultaneously and choose to emphasize one or the other, and this divide has only grown in recent times. But both of these views are equally valid and equally important, and ultimately in order to understand this country and see it progress, you have to be at peace with both views.

But it’s actually better than that, because there is a third, meta-level view which is even more important, that of progress. The original deficiencies of the constitution were corrected and equal rights extended to a variety of groups who didn’t have them, including women, people of color, Catholics, Jews and immigrants. Chattel slavery was abolished and Native Americans, while not reverting to their previous status, could live in dignity as American citizens.

This was the idea of constantly striving toward a “more perfect Union” that Lincoln emphasized. There were hiccups along the way, but overall there was undoubtedly great progress. Today American citizens are some of the freest people in the world, even with the challenges they face. If you don’t believe this, then you effectively believe that the country is little different from what it was fifty or a hundred years ago.

It seems that this election and these times are fundamentally about whether you can hold the complex, often contradictory history of this country in your mind without conflict, and more importantly whether you subscribe to the meta-level view of progress. Because if you can’t, you will constantly either believe that the country is steeped in irredeemable sin or sweep its inequities under the rug. Not only would both views be pessimistic but both would do a disservice to reality. But if you can in fact hold this complex reality in mind, you will believe that this is a great country not just in spite of its history but because of it.

A Foray into Jewish History and Judaism

I have always found the similarities between Hinduism and Judaism (and between Hindu Brahmins in particular and Jews) very striking. In order of increasing importance:

1. Both religions are very old, extending back unbroken between 2500 and 3000 years with equally old holy books and rituals.

2. Both religions place a premium on rituals and laws like dietary restrictions etc.

3. Hindus and Jews have both endured for a very long time in spite of repeated persecution, exile, oppression etc. although this is far more true for Jews than Hindus. Of course, the ancestors of Brahmins have the burden of caste while Jews have no such thing, but both Hindus and Jews have been persecuted for centuries by Muslims and Christians. At the same time, people of both faiths have also lived in harmony and productive intercourse with these other faiths for almost as long.

4. Both religions place a premium on the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge and learning. Even today, higher education is a priority in Jewish and Hindu families. As a corollary, both religions also place a premium on fierce and incessant argumentation and are often made fun of for this reason.

5. Both religions are unusually pluralistic, secular and open to a variety of interpretations and lifestyles without losing the core of their faith. You can be a secular Jew or an observant one, a zealous supporter or harsh critic of Israel, a Jew who eats pork and still calls himself a Jew. You can even be a Godless Jewish atheist (as Freud called himself). Most importantly, as is prevalent especially in the United States, you can be a “cultural Jew” who enjoys the customs not because of deep faith but because it fosters a sense of community and tradition. Similarly, you can be a highly observant Hindu, a flaming Hindu nationalist, an atheist Hindu who was raised in the tradition but who is now a “cultural Hindu” (like myself), a Hindu who commits all kinds of blasphemies like eating steak and a Hindu who believes that Hinduism can encompass all other faiths and beliefs.

I think that it’s this highly pluralistic and flexible belief and tradition system that has made both Judaism and Hinduism what Nassim Taleb calls “anti-fragile”, not just resilient but being able to be actively energized in the face of bad events. Not surprisingly, Judaism has always been a minor but constant interest of mine, and there is no single group of people I admire more. The interest has always manifested itself previously in my study of Jewish scientists like Einstein, Bethe, von Neumann, Chargaff and Ulam, many of whom fled persecution and founded great schools of science and learning. More broadly though, although I am familiar with the general history, I am planning to do a deeper dive into Jewish history this year. Here is a list of books that I have either read (*), am reading ($) or planning to read (+). I would be interested in recommendations.

1. Paul Johnson’s “The History of the Jews”. (*)

2. Simon Schama’s “The Story of the Jews”. (*)

3. Jane Gerber’s “The Jews of Spain”. ($)

4. Nathan Katz’s “The Jews of India”. (*)

5. Amos Elon’s “The Pity of It All: A Portrait of the German-Jewish experience, 1743-1933”. ($)

6. Norman Lebrecht’s “Genius and Anxiety: How Jews Changed the World: 1847-1947”. ($)

7. Erwin Chargaff’s “Heraclitean Fire”. (*)

8. Stanislaw Ulam’s “Adventures of a Mathematician”. (*)

9. Stefan Zweig’s “The World of Yesterday”. (*)

10. Primo Levi’s “Survival in Auschwitz” and “The Periodic Table”. (*)

11. Robert Wistrich’s “A Lethal Obsession: Anti-Semitism from Antiquity to the Global Jihad”. (*)

12. Jonathan Kaufman’s “The Last Kings of Shanghai”. (This seems quite wild) (+)

13. Istvan Hargittai’s “The Martians of Science”. (*)

14. Bari Weiss’s “How to Fight Anti-Semitism”. (+)

15. Ari Shavit’s “My Promised Land”. (+)

16. Norman Cohn’s “Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion” (*)

17. Irving Howe’s “World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made“ (+)

18. Edward Kritzler’s “Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean” (another book that sounds wild) (+)

19. Alfred Kolatch’s “The Jewish Book of Why” (+)

20. Simon Sebag-Montefiore’s “Jerusalem” ($)

Life. Distributed.

One of my favorite science fiction novels is “The Black Cloud” by Fred Hoyle. It describes an alien intelligence in the form of a cloud that approaches the earth and settles by the sun. Because of its proximity to the sun the cloud causes havoc with the climate and thwarts the attempts of scientists to both study it and attack it. Gradually the scientists come to realize that the cloud is an intelligence unlike any they have encountered. They are finally successful in communicating with the cloud and realize that its intelligence is conveyed by electrical impulses moving inside it. The cloud and the humans finally part on peaceful terms.

There are two particularly interesting aspects of the cloud that warrant further attention. One is that it’s surprised to find intelligence on a solid planet; it is used to intelligence being gaseous. The second is that it’s surprised to find intelligence concentrated in individual human minds; it is used to intelligence constantly moving around. The reason these aspects of the story are interesting is because they show that Hoyle was ahead of his time and was already thinking about forms of intelligence and life that we have barely scratched the surface of.

Our intelligence is locked up in a three pound mass of wet solid matter. And it’s a result of the development of the central nervous system. The central nervous system was one of the great innovations in the history of life. It allowed organisms to concentrate their energy and information-processing power in a single mass that sent out tentacles communicating with the rest of the body. The tentacles are important but the preponderance of the brain’s capability resides in itself, in a single organ that cannot be detached or disassembled and moved around. From dolphins to tigers and from bonobos to humans, we find the same basic plan existing for good reasons. The central nervous system is an example of what’s called convergent evolution, which refers to the ability of evolution to find the same solutions for complex problems. Especially in Homo sapiens, the central nervous system and the consequent development of the neocortex are seen as the crowning glory of human evolution.

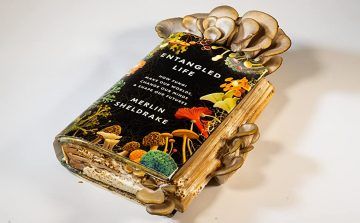

And yet it’s the solutions that escaped the general plan that are the most interesting in a sense. Throughout the animal and plant kingdom we find examples not of central but of distributed intelligence, like Hoyle’s cloud. Octopuses are particular fascinating examples. They can smell and touch and understand not just through their conspicuous brains but through their tentacles; they are even thought to “see” color through these appendages. But to find the ultimate examples of distributed intelligence, it might be prudent not to look at earth’s most conspicuous and popular examples of life but its most obscure – fungi. Communicating the wonders of distributed intelligence through the story of fungi is what Merlin Sheldrake accomplishes in his book, “Entangled Life”.

Fungi have always been our silent partners, partners that are much more like us than we can imagine. Like bacteria they are involved in an immense number of activities that both aid and harm human beings, but most interestingly, fungi unlike bacteria are eukaryotes and are therefore, counterintuitively, evolutionarily closer to us rather than to their superficially similar counterparts. And they get as close to us as we can imagine. Penicillin is famously produced by a fungus; so is the antibiotic fluconazole that is used to kill other fungal infections. Fungal infections can be deadly; Aspergillus forms clumps in the lungs that can rapidly kill patients by spreading through the bloodstream. Fungi of course charm purveyors of gastronomic delights everywhere in the world as mushrooms, and they also charm purveyors of olfactory delights as truffles; a small lump can easily sell for five thousand dollars. Last but not the least, fungi have taken millions of humans into other worlds and artistic explosions of colors and sight by inducing hallucinations.

With this diverse list of vivid qualities, it may seem odd that perhaps the most interesting quality of fungi lies not in what we can see but what we can’t. Mushrooms may grace dinner plates in restaurants and homes around the world, but they are merely the fruiting bodies of fungi. They may be visible as clear vials of life-saving drugs in hospitals. But as Sheldrake describes in loving detail, the most important parts of the fungi are hidden below the ground. These are the vast networks of the fungal mycelium – the sheer, gossamer, thread-like structure snaking its way through forests and hills, sometimes spreading over hundreds of square miles, occasionally being as old as the neolithic revolution, all out of sight of most human beings and visible only to the one entity with which it has forged an unbreakable, intimate alliance – trees. Dig a little deep into a tree root and put it under a microscope and your will find wisps of what seem like even smaller roots, except that these roots penetrate into the trees roots. The wisps are fungal mycelium. They are everywhere; around roots, under them, over them and inside them. At first glance the the ability of fungal networks to penetrate inside tree roots might evoke pain and invoke images of an unholy literal physical union of two species. It’s certainly a physical union, but it may be one of the holiest meetings of species in biology. In fact it might well be impossible to find a tree whose roots have no interaction with fungal mycelium. The vast network of fibers the mycelium forms is called a mycorrhizal network.

The mycorrhizal networks that wind their way in and out of tree roots are likely as old as trees themselves. The alliance almost certainly exists because of a simple matter of biochemistry. When plants first colonized land they possessed the miraculous ability of photosynthesis that completely changed the history of life on this planet. But unlike carbon which they can literally manufacture out of sunlight and thin air, they still have to find essential nutrients for life, metals like magnesium and other life-giving elements like phosphorus and nitrogen. Because of an intrinsic lack of mobility, plants and trees had to find someone who could bring them these essential elements. The answer was fungi. Fungal networks stretching across miles ensured that they could shuttle nutrients back and forth between trees. In return the fungi could consume the precious carbon that the tree sank into its body – as much as twenty tons during a large tree’s lifetime. It was the classic example of symbiosis, a term coined by the German botanist Albert Frank, who also coined the term mycorrhiza.

However, the discovery that fungal networks could supply trees with essential nutrients in a symbiotic exchange was only the beginning of the surprises they held. Sheldrake talks in particular about the work of the mycologists Lynne Body and Suzanne Simard who have found qualities in the mycorrhizal networks of trees that can only be described as deliberate intelligence. Here are a few examples: fungi seem to “buy low, sell high”, providing trees with important elements when they have fallen on hard times and liberally borrowing from them when they are doing well. Mycorrhizal networks also show electrical activity and can discharge a small burst of electrochemical potential when prodded. They can entrap nematodes in a kind of death grip and extract their nutrients; they can do the same with ants. Perhaps most fascinatingly, fungal mycelia display “intelligence at a distance”; one part of a huge fungal network seems to know what the other is doing. The most striking experiment that demonstrates this shows oyster mushroom mycelium growing on a piece of wood and spreading in all directions. When another piece of wood is kept at a distance, within a few days the fungal fibers spread and latch on to that piece. This is perhaps unsurprising. What is surprising is that once the fungus discovers this new food source, it almost instantly pares down growth in all other parts of its network and concentrates it in the direction of the new piece of wood. Even more interestingly, scientists have found that the hyphae or tips of fungi can act not only as sensors but as primitive Boolean logic gates, opening and closing to allow only certain branches of the network to communicate with each other. There are even attempts to use fungi as primitive computers.

This intelligent long-distance relay gets mirrored in the behavior of the trees that the fungi form a mind meld with. One of the characters in Richard Powers’s marvelous novel “The Overstory” discovers how trees are whispering hidden signals to each other, not just through fungal networks but through ordinary chemical communication. The character Patty Westford finds out that when insects attack one tree, it can send out a chemical alarm that alerts trees located even dozens of meters away of its plight, causing them to kick their own repellant chemical production into high gear. Meeting the usual fate of scientists with novel ideas, Westford and her ideas are first ignored, then mocked and ostracized and ultimately grudgingly accepted. But the discovery of trees and their fungal networks communicating through each other and through the agency of both chemicals and other organisms like insects is now generally accepted enough to become part of both serious scientific journals and prizewinning novels.

Fungi can also show intelligent behavior by manipulating our minds, and this is where things get speculative. Psilocybin and LSD have been used by shamans, hippies and Silicon Valley tech entrepreneurs over thousands of years. When you are familiar with both chemistry and biology it’s natural to ask what might be the perceived evolutionary utility of chemical compounds that bring about changes in perception that are so profound and seemingly liberating as to lead someone like Aldous Huxley to make sure that he was on a psychedelic high during the moment of his death. One interesting clue arises from the discovery of these compounds in the chemical defense responses of certain fungi. Clearly the microorganisms that are engaged in a war with fungi – and these often include other fungi – lack a central nervous system and have no concept of a hallucination. But if these compounds are found as part of the wreckage of fungal wars, maybe this was their original purpose, and the fact that they happen to take humans on a trip is only incidental.

That is the boring and likely explanation. The interesting and unlikely explanation that Sheldrake alludes to is to consider a human, in the medley of definitions that humans have lent themselves to, as a vehicle for a fungus to propagate itself. In the Selfish Fungus theory, magic mushrooms and ergot have been able to hijack our minds so that more of us will use them, cultivate and tend them and love them, ensuring their propagation. Even though their effects might be incidental, they can help us in unexpected ways. If acid and psilocybin trips can spark even the occasional discovery of a new mathematical object or a new artistic style, both the fungi and the humans’ purpose is served. I have another interesting theory of psychedelic mushroom-human co-evolution in mind that refers to Julian Jaynes’s idea of the bicameral mind. According to Jaynes, humans may have lacked consciousness until as recently as 3000 years ago because their mind was divided into two parts, one of which “spoke” and the other “listened”. What we call Gods speaking to humans was a result of the speaking side holding forth. Is it possible that at some point in time, humans got hold of psychedelic fungi and they hijacked a more primitive version of the speaking mind that allowed it it to turn into a full-blown voice inside the other mind’s head, so to speak? Jaynes’s theory has been called “either complete rubbish or a work of consummate genius, nothing in between” by Richard Dawkins, and this might be another way to probe whether it might be true for a reason.

It is all too easy to anthropomorphize trees and especially fungi, which only indicates how interestingly they behave. One can say that “trees give and trees receive”, “trees feel” and even “trees know”, but at a biological level is this behavior little more than a series of Darwinian business transactions, purely driven by natural selection and survival? Maybe, but ultimately what matters is not what we call the behavior but the connections it implies. And there is no doubt that fungi, trees, octopuses and a few other assorted creatures are displaying a unique type of intelligence that humans may have merely glimpsed. Distributed intelligence clearly has a few benefits over a central, localized one. Unlike humans who are unlikely to live when their heads are cut off, newts can regrow their heads when they get detached, so there’s certainly a survival advantage conferred by not having your intelligence organ be one and done. This principle has been exploited by the one form of distributed intelligence that is an extension of human beings and that has taken over the planet – the Internet. Among many ideas that are regarded as the origins of the Internet, one was conceived by the defense department which wanted to built a communications net that would be resilient in the face of nuclear attack. Having a distributed network with no one node being a central node was the key. Servers in companies like Google and Facebook are also constructed in such a way that a would be hacker or terrorist would have to take out several and not just a few in order to measurably impair the fidelity of the network.

I also want to posit the possibility that distributed systems might be more analog than central ones and therefore confer unique advantages. Think of a distributed network of water pipes, arteries, traffic lanes or tree roots and fungal networks and one has the image in mind of a network that can almost instantaneously transmit changes in parameters like pressure, temperature and density taking place in one part of the network to another. These are all good examples of analog computation, although in case of arteries, the analog process is built on a substrate of digital neuronal firing. The human body is clearly a system where a combination of analog and digital works well, but looking at distributed intelligence one gets a sense that we can optimize our intelligence significantly using more analog computing.

There is no reason why intelligence may not be predominantly analog and distributed so that it becomes resilient, sensitive and creative like mycorrhizal networks, being able to guard itself against existential threats, respond to new food and resource locations and construct new structures with new form and function. One way to make human intelligence more analog and distributed would be to enable human-to-human connections through high-fidelity electronics that allows a direct flow of information to and from human brains. But a more practical solution might be to enable downloading brain contents including memory into computers and then allowing these computers to communicate with each other. I do not know if this advance will take place during my lifetime, but it could certainly bring us closer to being a truly distributed intelligence that just like mycorrhizal networks is infinitely responsive, creative, resilient and empathetic. And then perhaps we will know exactly what it feels like to be a tree.

Brains, Computation And Thermodynamics: A View From The Future?

- Charles Bennett – The Thermodynamics of Computation

- Seth Lloyd – Ultimate Physical Limits to Computation

- Freeman Dyson – Are brains analog or digital?

- George Dyson – Analogia: The Emergence of Technology Beyond Programmable Control (August 2020)

- Richard Feynman – The Feynman Lectures on Computation (Chapter 5)

- John von Neumann – The General and Logical Theory of Automata