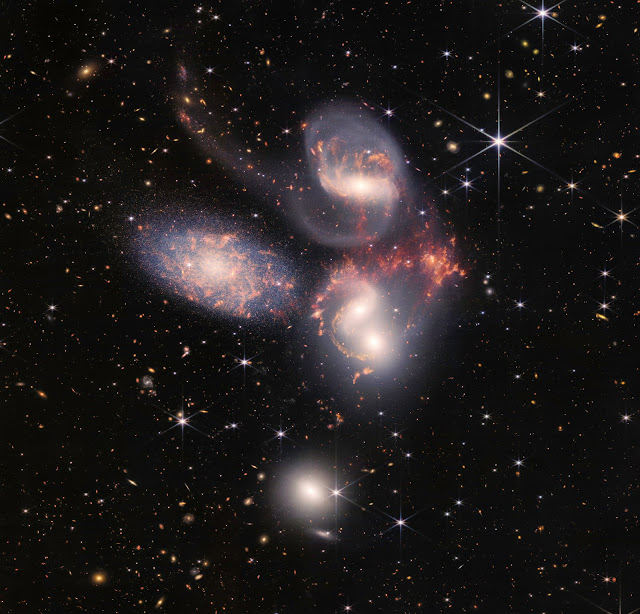

For a brief period earlier this week, social media and the world at large seemed to stop squabbling about politics and culture and united in a moment of wonder as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) released its first stunning images of the cosmos. These "extreme deep field" images represent the farthest and the oldest that we have been able to see in the universe, surpassing even the amazing images captured by the Hubble Space Telescope that we have become so familiar with. We will soon see these photographs decorating the walls of classrooms and hospitals everywhere.

The scale of the JWST images is breathtaking. Each dot represents a galaxy or nebula from far, far away. Each galaxy or nebula is home to billions of stars in various stages of life and death. The curved light in the image comes from a classic prediction of Einstein's general theory of relativity called gravitational lensing - the bending of light by gravity that makes spacetime curvature act like a lens.

Some of the stars in these distant galaxies and nebulae are being nurtured in stellar nurseries; others are in their end stages and might be turning into neutron stars, supernovae or black holes. And since galaxies have been moving away from us because of the expansion of the universe, the farther out we see, the older the galaxy is. This makes the image a gigantic hodgepodge of older and newer photographs, ranging from objects that go as far back as 100 million years after the Big Bang to very close (on a cosmological timescale) objects like Stephan's Quintet and the Carina Nebula that are only a few tens of thousands of light years away.

It is a significant and poignant fact that we are seeing objects not as they are but as they were. The Carina Nebula is 8,500 light years away, so we are seeing it as it looked like 8,500 years ago, during the Neolithic Age when humanity had just taken to farming and agriculture. On the oldest timescale, objects that are billions of light years away look the way did during the universe's childhood. The fact that we are seeing old photographs or stars, galaxies and nebulae gives the photo a poignant quality. For a younger audience who has always grown up with Facebook, imagine seeing a hodgepodge of images of people from Facebook over the last fifteen years presented to you: some people are alive and some people no longer so, some people look very different from what they did when their photo was last taken. It would be a poignant feeling. But the JWST image also fills me with joy. Looking at the vast expanse, the universe feels not like a cold, inhospitable place but like a living thing that's pulsating with old and young blood. We are a privileged part of this universe.

There's little doubt that one of the biggest questions stimulated by these images would be whether we can detect any signatures of life on one of the many planets orbiting some of the stars in those galaxies. By now we have discovered thousands of extrasolar planets around the universe, so there's no doubt that there will be many more in the regions the JWST is capturing. The analysis of the telescope data already indicates a steamy atmosphere containing water on a planet about 1,150 light years away. Detecting elements like nitrogen, carbon, sulfur and phosphorus is a good start to hypothesizing about the presence of life, but much more would be needed to clarify whether these elements arise from an inanimate process or a living one. It may seem impossible that a landscape as gargantuan as this one is completely barren of life, but given the improbability of especially intelligent life arising through a series of accidents, we may have to search very wide and long.

I was gratified as my twitter timeline - otherwise mostly a cesspool of arguments and ad hominem attacks punctuated by all-too-rare tweets of insight - was completely flooded with the first images taken by the JWST. The images proved that humanity is still capable of coming together and focusing on a singular achievement of science and technology, how so ever briefly. Most of all, they prove both that science is indeed bigger than all of us and that we can comprehend it if we put our minds and hands together. It's up to us to decide whether we distract ourselves and blow ourselves up with our petty disputes or explore the universe as revealed by JWST and other feats of human ingenuity in all its glory.

Image credits: NASA, ESA, CSA and STScl

No comments:

Post a Comment

Markup Key:

- <b>bold</b> = bold

- <i>italic</i> = italic

- <a href="http://www.fieldofscience.com/">FoS</a> = FoS