Newton rightly decried that science progresses by standing on the shoulders of giants. But his often-quoted statement applies even more broadly than he thought. A case in point: when it comes to the discovery of DNA, how many have heard of Friedrich Miescher, Fred Griffith or Lionel Alloway? Miescher was the first person to isolate DNA, from pus bandages of patients. Fred Griffith performed the crucial experiment that proved that a ‘transforming principle’ was somehow passing from a virulent dead bacterium to a non-virulent live bacterium, magically rendering the non-virulent strain virulent. Lionel Alloway came up with the first expedient method to isolate DNA by adding alcohol to a concentrated solution.

- Home

- Angry by Choice

- Catalogue of Organisms

- Chinleana

- Doc Madhattan

- Games with Words

- Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

- History of Geology

- Moss Plants and More

- Pleiotropy

- Plektix

- RRResearch

- Skeptic Wonder

- The Culture of Chemistry

- The Curious Wavefunction

- The Phytophactor

- The View from a Microbiologist

- Variety of Life

Field of Science

-

-

Change of address7 months ago in Variety of Life

-

Change of address7 months ago in Catalogue of Organisms

-

-

Earth Day: Pogo and our responsibility10 months ago in Doc Madhattan

-

What I Read 202410 months ago in Angry by Choice

-

I've moved to Substack. Come join me there.1 year ago in Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

-

-

-

-

Histological Evidence of Trauma in Dicynodont Tusks7 years ago in Chinleana

-

Posted: July 21, 2018 at 03:03PM7 years ago in Field Notes

-

Why doesn't all the GTA get taken up?7 years ago in RRResearch

-

-

Harnessing innate immunity to cure HIV9 years ago in Rule of 6ix

-

-

-

-

-

-

post doc job opportunity on ribosome biochemistry!11 years ago in Protein Evolution and Other Musings

-

Blogging Microbes- Communicating Microbiology to Netizens11 years ago in Memoirs of a Defective Brain

-

Re-Blog: June Was 6th Warmest Globally11 years ago in The View from a Microbiologist

-

-

-

The Lure of the Obscure? Guest Post by Frank Stahl13 years ago in Sex, Genes & Evolution

-

-

Lab Rat Moving House14 years ago in Life of a Lab Rat

-

Goodbye FoS, thanks for all the laughs14 years ago in Disease Prone

-

-

Slideshow of NASA's Stardust-NExT Mission Comet Tempel 1 Flyby15 years ago in The Large Picture Blog

-

in The Biology Files

Book review: "Unraveling the Double Helix: The Lost Heroes of DNA", by Gareth Williams.

Brian Greene and John Preskill on Steven Weinberg

There's a very nice tribute to Steven Weinberg by Brian Greene and John Preskill that I came across recently that is worth watching. Weinberg was of course one of the greatest theoretical physicists of the later half of the 20th century, winning the Nobel Prize for one of the great unifications of modern physics, which was the unification of the electromagnetic and the weak forces. He was also a prolific author of rigorous, magisterial textbooks on quantum field theory, gravitation and other aspects of modern physics. And on top of it all, he was a true scholar and gifted communicator of complex ideas to the general public through popular books and essays; not just ideas in physics but ones in pretty much any field that caught his fancy. I had the great pleasure and good fortune to interact with him twice.

The conversation between Greene and Preskill is illuminating because it sheds light on many underappreciated qualities of Weinberg that enabled him to become a great physicist and writer, qualities that are worth emulating. Greene starts out by talking about when he first interacted with Weinberg when he gave a talk as a graduate student at the physics department of the University of Texas at Austin where Weinberg taught. He recalls how he packed the talk with equations and formal derivations, only to have the same concepts explained by Weinberg more clearly later. As physicists appreciate, while mathematics remains the key to unlock the secrets of the universe, being able to understand the physical picture is key. Weinberg was a master at doing both.

Preskill was a graduate student of Weinberg's at Harvard and he talks about many memories of Weinberg. One of the more endearing and instructive ones is from when he introduced Weinberg to his parents at his house. They were making ice cream for dinner, and Weinberg wondered aloud why we add salt while making the ice cream. By that time Weinberg had already won the Nobel Prize, so Preskill's father wondered if he genuinely didn't understand that you add the salt to lower the melting point of the ice cream so that it would stay colder longer. When Preskill's father mentioned this Weinberg went, "Of course, that makes sense!". Now both Preskill and Greene think that Weinberg might have been playing it up a bit to impress Preskill's family, but I wouldn't be surprised if he genuinely did not know; top tier scientists who work in the most rarefied heights of their fields are sometimes not as connected to basic facts as graduate students might be.

More importantly, in my mind the anecdote illustrates an important quality that Weinberg had and that any true scientist should have, which is to never hesitate to ask even simple questions. If, as a Nobel Prize winning scientist, you think you are beyond asking simple questions, especially when you don't know the answers, you aren't being a very good scientist. The anecdote demonstrates a bigger quality that Weinberg had which Preskill and Greene discuss, which was his lifelong curiosity about things that he didn't know. He never hesitated to pump people for information about aspects of physics he wasn't familiar with, not to mention another disciplines. Freeman Dyson who I knew well had the same quality: both Weinberg and Dyson were excellent listeners. In fact, asking the right question, whether it was about salt and ice cream or about electroweak unification, seems to have been a signature Weinberg quality that students should take to heart.

Weinberg became famous for a seminal 1967 paper that unified the electromagnetic and weak force (and used ideas developed by Peter Higgs to postulate what we now call the Higgs boson). The title of the paper was "A Model of Leptons", but interestingly, Weinberg wasn't much of a model builder. As Preskill says, he was much more interested in developing general, overarching theories than building models, partly because models have a limited applicability to a specific domain while theories are much more general. This is a good point, but of course, in fields like my own field of computational chemistry, the problem isn't that there are no general theoretical frameworks - there are, most notably the frameworks of quantum mechanics and statistical mechanics - but that applying them to practical problems is too complicated unless we build specific models. Nevertheless, Weinberg's attitude of shunning specific models for generality is emblematic of the greatest scientists, including Newton, Pauling, Darwin and Einstein.

Weinberg was also a rather solitary researcher; as Preskill points out, of his 50 most highly cited papers, 42 are written alone. He admitted himself in a talk that he wasn't the best collaborator. This did not make him the best graduate advisor either, since while he was supportive, his main contribution was more along the lines of inspiration rather than guidance and day-to-day conversations. He would often point students to papers and ask them to study them themselves, which works fine if you are Brian Greene or John Preskill but perhaps not so much if are someone else. In this sense Weinberg seems to be have been a bit like Richard Feynman who was a great physicist but who also wasn't the best graduate advisor.

Finally, both Preskill and Greene touch upon Weinberg's gifts as a science writer and communicator. More than many other scientists, he never talked down to his readers because he understood that many of them were as smart as him even if they weren't physicists. Read any one of his books and you see him explaining even simple ideas, but never in a way that assumes his audience are dunces. This is a lesson that every scientist and science writer should take to heart.

Greene especially knew Weinberg well because he invited him often to the World Science Festival which he and his wife had organized in New York over the years. The tribute includes snippets from Weinberg talking about the current and future state of particle physics. In the last part, an interviewer asks him about what is arguably the most famous sentence from his popular writings. In the last part of his first book, "The First Three Minutes", he says, "The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it seems pointless." Weinberg's eloquent response when he was asked what this means sums up his life's philosophy and tells us why he was so unique, as a scientist and as a human being:

"Oh, I think everything's pointless, in the sense that there's no point out there to be discovered by the methods of science. That's not to say that we don't create points for our lives. For many people it's their loved ones; living a life of helping people you love, that's all the point that's needed for many people. That's probably the main point for me. And for some of us there's a point in scientific discovery. But these points are all invented by humans and there's nothing out there that supports them. And it's better that we not look for it. In a way, we are freer, in a way it's more noble and admirable to give points to our lives ourselves rather than to accept them from some external force."

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away

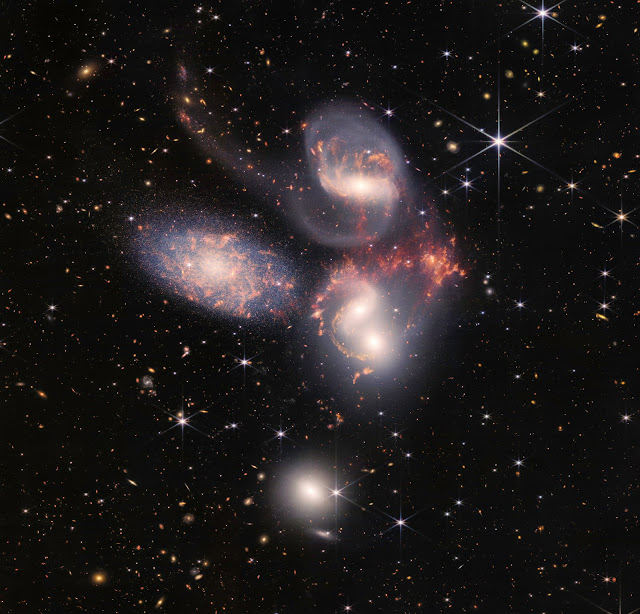

For a brief period earlier this week, social media and the world at large seemed to stop squabbling about politics and culture and united in a moment of wonder as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) released its first stunning images of the cosmos. These "extreme deep field" images represent the farthest and the oldest that we have been able to see in the universe, surpassing even the amazing images captured by the Hubble Space Telescope that we have become so familiar with. We will soon see these photographs decorating the walls of classrooms and hospitals everywhere.

The scale of the JWST images is breathtaking. Each dot represents a galaxy or nebula from far, far away. Each galaxy or nebula is home to billions of stars in various stages of life and death. The curved light in the image comes from a classic prediction of Einstein's general theory of relativity called gravitational lensing - the bending of light by gravity that makes spacetime curvature act like a lens.

Some of the stars in these distant galaxies and nebulae are being nurtured in stellar nurseries; others are in their end stages and might be turning into neutron stars, supernovae or black holes. And since galaxies have been moving away from us because of the expansion of the universe, the farther out we see, the older the galaxy is. This makes the image a gigantic hodgepodge of older and newer photographs, ranging from objects that go as far back as 100 million years after the Big Bang to very close (on a cosmological timescale) objects like Stephan's Quintet and the Carina Nebula that are only a few tens of thousands of light years away.

It is a significant and poignant fact that we are seeing objects not as they are but as they were. The Carina Nebula is 8,500 light years away, so we are seeing it as it looked like 8,500 years ago, during the Neolithic Age when humanity had just taken to farming and agriculture. On the oldest timescale, objects that are billions of light years away look the way did during the universe's childhood. The fact that we are seeing old photographs or stars, galaxies and nebulae gives the photo a poignant quality. For a younger audience who has always grown up with Facebook, imagine seeing a hodgepodge of images of people from Facebook over the last fifteen years presented to you: some people are alive and some people no longer so, some people look very different from what they did when their photo was last taken. It would be a poignant feeling. But the JWST image also fills me with joy. Looking at the vast expanse, the universe feels not like a cold, inhospitable place but like a living thing that's pulsating with old and young blood. We are a privileged part of this universe.

There's little doubt that one of the biggest questions stimulated by these images would be whether we can detect any signatures of life on one of the many planets orbiting some of the stars in those galaxies. By now we have discovered thousands of extrasolar planets around the universe, so there's no doubt that there will be many more in the regions the JWST is capturing. The analysis of the telescope data already indicates a steamy atmosphere containing water on a planet about 1,150 light years away. Detecting elements like nitrogen, carbon, sulfur and phosphorus is a good start to hypothesizing about the presence of life, but much more would be needed to clarify whether these elements arise from an inanimate process or a living one. It may seem impossible that a landscape as gargantuan as this one is completely barren of life, but given the improbability of especially intelligent life arising through a series of accidents, we may have to search very wide and long.

I was gratified as my twitter timeline - otherwise mostly a cesspool of arguments and ad hominem attacks punctuated by all-too-rare tweets of insight - was completely flooded with the first images taken by the JWST. The images proved that humanity is still capable of coming together and focusing on a singular achievement of science and technology, how so ever briefly. Most of all, they prove both that science is indeed bigger than all of us and that we can comprehend it if we put our minds and hands together. It's up to us to decide whether we distract ourselves and blow ourselves up with our petty disputes or explore the universe as revealed by JWST and other feats of human ingenuity in all its glory.

Image credits: NASA, ESA, CSA and STScl